What Makes A Man?

If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you; If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, but make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting, or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies, or, being hated, don’t give way to hating, and yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master; if you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with triumph and disasters and treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools, or watch the things you gave your life to broken, and stoop and build ’em up with wornout tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings and risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss, and lose, and start again at your beginnings and never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew to serve your turn long after they are gone, and so hold on when there is nothing in you except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”;

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, or walk with kings—nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you; if all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run—

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!¹

How To Become ‘The Man’ (According to Rudyard Kipling)

Among the many obstacles to a contented experience of adult life among men in the West is the stark absence of any concrete definition beyond the biological—however, this, too, is now routinely called into question—for masculinity itself. How is a man to be contented with his ambitions if he isn’t able, first, to cite some ultimate goals to which to aspire? The poem above, so beautifully penned by Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) presents a particular view of masculine virtue, nested in both humility and courageous heroism. It reveals a man who possesses a host of characteristics that one might argue constitute a good and integral life.

Kipling’s Man:

- Possesses settled interiority. Is able to “keep his head” or remain of measured temper and disposition in the face of adversity.

- He does so even in the midst of undue slander.

- Is able to hold to his studied convictions when others disagree with him.

- He does so while valuing both, their freedom of speech and the representative perspective of others. He “makes allowance” for their distrust of him and doesn’t censor them.

- Knows longsuffering. Is able to wait with patience for the proper conclusion of a matter.

- Is able to be lied about and not lie about others in return.

- Is able to be hated by others and not become hateful himself.

- To not win people over by vain personal presentation of appearance or of sophisticated speech. In other words, such a man refuses to manipulate others or to apply force in his dealings with others. Think here of Paul (I didn’t come with dazzling words³) and of Jesus (let your yes be yes and your no be no⁴).

- Lives a life of calling rather than a life of mere construction—in dreaming and not making dreams his master, he is surrendered, not to his wants, but to his responsibilities.

- Is able to think deeply without thinking of his thoughts as deep. He thinks for a cause, not to be thought of as a great thinker. He humbly ventures into the world of ideas with a view to what is good, rather than a focus on self-advancement.

- Is able to encounter triumph and disaster in equal measure as ‘life’.

- He is not deluded in thinking of ‘triumph’ as life treating him fairly and disaster as imbalanced injustice. He regards both these as potential “imposters,” as containing the potential to unduly possess both his thoughts and his ambitions.

- Possesses an advanced knowledge of the likelihood in this life of dubious misrepresentation and rumor.

- He chooses not to become possessed by vengeful justification or retribution.

- Is prepared for that which he has ‘built’ (a reputation, a business, a program, a document, a technology, a home,…) to be ruinously destroyed by the unexpected and the unpredictable in life.

- He is resolved to build it again or to build something else with whichever tools he still possesses.

- Is prepared to lose everything if the right matter calls for such a risk (a seemingly wise investment, a partner agreement, a new vocational venture).

- Is prepared, if he loses everything to the worthy risk waged, to build again and to continue to grow with resolve.

- Is not going to regard himself as the victim in the event of his loss. He doesn’t make it the central focus of his social arrangements in the meantime.

- Perseveres, even when he understands himself to be weakened by age or by lack of resource. He “holds on” when holding to his virtue is all that he has left. He has identified his ‘pearl of great price’.⁵

- He is able to be met with great esteem in the social realm—perhaps he becomes a well known thought leader in business, or a business program developer known to many. Even in this, he doesn’t lose his virtue; doesn’t develop an inflated sense of himself (think here of Jesus’ command not to let our left hand know what our right hand is doing in our offerings to the world⁶).

- Is able to travel in esteemed circles of power and prestige and not forget his common humanity or his interest in engaging with the ‘everyman’.

- Is differentiated in such a way as not to lose his identity to ‘hurts’ caused, whether by friend or foe.

- He remains in the good graces of the majority without losing himself to that as his quest. He never gives himself ultimately to the pursuit of social consensus or to be regarded well inside of the status quo.

- Is resolutely able to put in a concerted offering of his whole self into a righteous task—one minute of which in this world constitutes a heroic act.

On these grounds, he ‘inherits’ the world he inhabits as his own. He is not ‘had’ by the world—is not a victim in it—but ‘has’ his own life inside of it with plain acceptance of the way that things are.

I would invite that we contrast such a man with the host of incoherent platitudes and ‘trainings’ that our boys receive in the halls of Modern socialization that they inhabit, whether educational, technological, sociological or otherwise.

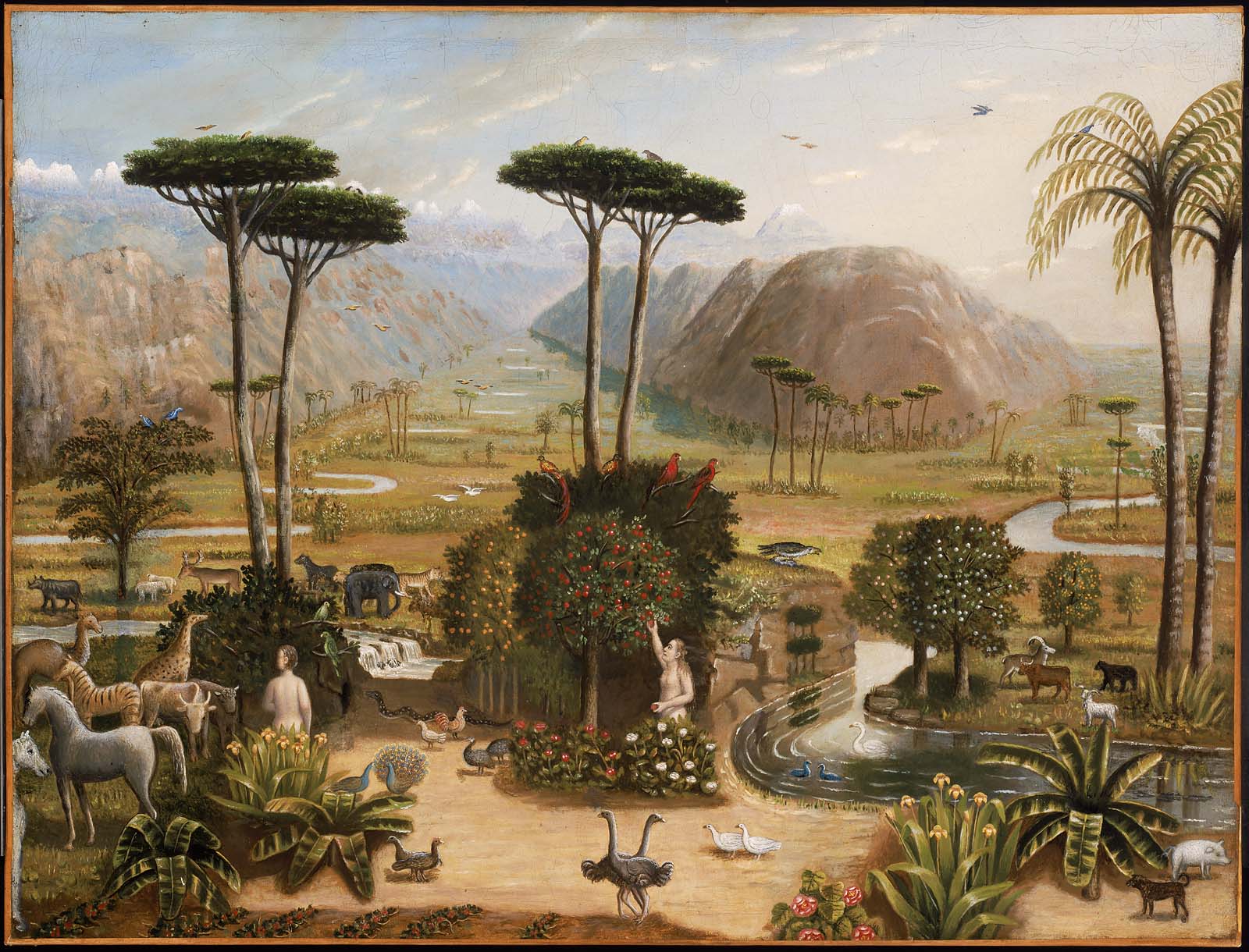

Josh Hawley, a U.S. senator, and author of Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs⁷ invites reflection on a man’s purpose by examining the teleological aspects of the ‘world’ presented in the Biblical story of Eden. In his hermeneutic glimpse into this ancient creation myth, Hawley notes that it is commonly understood among scholars that the ‘garden’ is presented as a temple inside of which Adam is to carry out the duties of a priest through two chief tasks:

- To ‘work’ the garden—to steward, curate and establish it as a flourishing and ever-more-inhabitable dwelling, and;

- To ‘keep’ the garden—to guard it and thus protect it from the dangers that lurk and wait beyond its boundaries.⁸

Hawley explains, “…at the heart of Adam’s mission was the obligation to place himself between the good things God had given him—his wife, his family, his home—and evil. Adam was to be part of God’s solution to the danger in the world.”⁹ Hawley contrasts this explicit service orientation at the heart of the identity of Man with the victimized entitlements that mark the Modern identity—with the host of victimized entitlements that corral the interests of the Western Self in its atomized quest for individual expression and fulfillment.

This orientation of the self—to sacrificial-stewardship-as-masculine-guardianship—requires that a man not only orient himself with resolute conviction to securing the wellbeing of the others ‘given’ him inside of his garden-temple, but that he be decisively engaged in guarding against evil having any say in himself.

Nonetheless, his other-focus remains the ground for his care of himself. Such a man understands that if he does not confront his own potential to be a vessel for evil, then those given him along with the world they inhabit, will perish. At no point in the story are we unburdened from responsibility to choose to engage and to honour the intrinsic purpose with which the natural order—the very order that factions of the Modern Self decry as grand-oppressor—is imbued.

We overcome such Epicurean ambitions and definitions by first engaging in a rule for life inside of which we are given by choice into the call to responsible love. Rather than the Epicurean idea of character formation—which “…comes down to this: ignore your vices, pursue pleasure, and prioritize happiness—and be a generically ‘nice person’ who won’t stand in the way of anyone else pursuing self-gratification”¹⁰—we are called by our responsibilities into a focus on service to our neighbours in a manner that guards us from wayward and potentially disastrous interests or pursuits.

Hawley notes what a galvanizing role the French philosopher, Jean Jacques Rosseau, played in the capture of the West by such hedonistic and isolated interests. Rosseau, notes Hawley, viewed his contemporaries as wrongfully captured by guilt and shame associated with subservience to societal institutions, to burdensome notions of morality and to the ‘oppressive’ ideals that marked them (marriage, moral laws conveyed in ancient scripture, etc.) because they stood in stark competition with what were the deeper and truer aspects of our oppressed humanity: our desires. For Rosseau (1712–1788), the modern man would correct his course only once he had been liberated “…from the moral shackles society had forged for him by getting him back in touch with himself.”¹¹ “The path to personal wholeness,” in Hawley’s assessment of Rousseau, “is personal fulfillment.”¹² Hawley invites his readers to make their own assessment of the quality of Rosseau’s worldview in noting,

“Rousseau took his own advice in this regard. He fathered five children in his life and abandoned all five of them to orphanages. He didn’t want the burden of raising them: they might interfere with his personal choices. So he gave them away, and kept himself free to be his own man, according to his own desires. It was all very Epicurean—and reprehensible.”¹³

The contrast between these status quo machinations in our society and the ancient call to masculine responsibility represented in the Genesis narrative is obvious. If we are to find fulfillment inside of the host of particular responsibilities that keeping the garden entails, then the keeping of oneself is a prior condition for success in this regard. The man presented to us as Adam is to be pulled into characterological alignment and integrity by no other means than his proper dedication to his own wellbeing by giving himself into the service of those he loves. In this, a character is finally forged in him that can constitute “a solution to evil.”¹⁴ “That,” states Hawley, “[is] the kind of character that can unlock the promise of the world.”¹⁵

“In Genesis, the charge to guard Eden is certainly a duty. But it is also an invitation: to forge the kind of character that can be a solution to evil. We will have better families, better churches and places of work—a better nation—when we have men with character like that. That’s the kind of character that can unlock the promise of the world.” — Senator Josh Hawley

Footnotes

¹ Rudyard Kipling, If—, first published 1910.

² Cf. James 1:12; Romans 5:3–5.

³ 1 Corinthians 2:1.

⁴ Matthew 5:37.

⁵ Matthew 13:45–46.

⁶ Matthew 6:3.

⁷ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs (New York: Sentinel, 2023).

⁸ Genesis 2:15.

⁹ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹⁰ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹¹ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹² Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹³ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹⁴ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.

¹⁵ Josh Hawley, Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs.